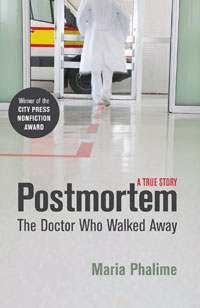

Postmortem: The doctor who walked away

- By Maria Phalime

- Review by Dr Anand Naranbhai, Intern at New Somerset Hospital, Western Cape, South Africa

After practising clinical medicine for four years, Maria Phalime decided to stop. Postmortem: The Doctor Who Walked Away tells the story of her search for an explanation and provides a useful commentary on the profession.

The book is divided into two parts. In the first part, Phalime searches within herself for reasons why she left. She tells of her life growing up in Soweto and then studying medicine at the University of Cape Town. She also documents her experiences as an intern in the United Kingdom and then as a community service officer in Mannenberg and Khayelitsha. Finally, she discusses the years during which she worked her way out of clinical medicine and into a new career.

In the second part of the book, Phalime searches outside herself, wondering if there were external factors that played a role in her decision to leave. She interviews others with various experiences in medicine as a way of providing perspective on her own story. I found reading the first part of the book laborious, although I was interested in her childhood and high school years.

From then on the cliches and anecdotes were unoriginal to my ears, although these do provide, for the general public, one account of what practising medicine in the public sector can be like.

The second part was far more enlightening. I enjoyed reading the interviews she conducted with those who have either left clinical medicine, or are still practising. For comedian Riaad Moosa, it was a natural progression away from medicine and into comedy; for ‘Nina’ (pseudonym), it was the combination of clinical depression and being a junior doctor in the South African public health sector.

This second part of the book highlighted common but often benignly accepted issues that we face in the medical profession. In the end, Phalime’s decision to leave is multifaceted. She concludes: “It was tough, it was sad, and I left, that’s all.” She practised medicine during the dark age of HIV-denialism, and in the often frustrating, pressured and disheartening South African public health sector.

There is a bigger lesson in the book: in an interview with Stellenbosch University Dean of Health Sciences, Professor Jimmy Volmink, Phalime is told: “We are all on a journey, and sometimes that journey takes us overseas, into the private sector, or even out of the profession altogether. People have got to be allowed to take that journey.”

Phalime is on her journey, each of us is on our own, and for our patients, maybe the point of what we do by caring for their health, is to give them an opportunity to take their own journey.